©2013 Jonathan Storvick and Organic Edible Gardens LLC

“Swales” and other rainwater-harvesting earthworks are an integral part of the sustainable landscape. Harvesting rainwater is by no means a new concept – humans have been capturing and storing rainwater for at least 6000 years, probably longer. From the cisterns of ancient Rome to today’s ubiquitous 55-gallon rain barrels, people have utilized the free and precious resource of rainwater for every water need from irrigation to bathing and drinking. Yet the use of tanks, cisterns and barrels can only be a small part of any sustainable water strategy.

This is because catchment itself is only part of the need. First, there is the simple matter of quantity – more water falls from the sky than we can possibly capture and use for our needs. For example, a 1-inch rainstorm falling on a 1000 square-foot roof generates more than 600 gallons of water – enough to fill a 55-gallon rain barrel almost 11 times. We could simply build a 600-gallon cistern to hold all of that water, but what if it rains 2 inches? Or 10 inches over a week-long storm? Where is that water going? And do we really need to hold on to 600 gallons? For what use? This also does not take into account the water that is falling on the rest of the yard.

Second, there is the issue of rainwater that flows over the landscape. Professionals and organizations are fond of referring to this issue as “stormwater management” – this water is a nuisance that must be diverted and shunted out to the nearest river as quickly as possible. We could not possibly disagree more with this stance. Stormwater flow is indeed a serious issue, as Colorado residents could tell you after the recent devastating floods in that state. However, a responsible stormwater management policy, combined with rainwater harvesting (viewing rainwater as a precious resource), would help to both collect and conserve water, as well as prevent flooding, erosion, and property damage.

Rainwater-harvesting earthworks are a key component of such a strategy. These earthworks include “swales,” terraces, rain gardens, and check dams. The term “swale” can be somewhat confusing – landscape and stormwater professionals use the term to denote a vegetated ditch that transports water. Permaculturists and rainwater harvesters use the word to describe a ditch dug on contour (running along an equal point of elevation crossways along a slope) with a berm placed on the downhill side of the ditch. When stormwater runs over the landscape, it is caught in these swales, and is allowed to slowly sink into the soil. Rainwater harvesting expert Brad Lancaster uses the term berm n’ basin to avoid confusion.

The catchphrase for both rainwater harvesting and stormwater management is “Slow, Spread, and Sink.” The idea is to slow the flow of water over the landscape, spread the water out evenly (instead of having it rush down one spot creating gullies), and sink it into the ground. Swales are an incredibly useful technique to accomplish this. The swale slows the flow of water by stopping it along a single point of elevation. It spreads the water, since it is a long ditch – much like a bathtub, even though water flows in from one point, the entire tub is filled with water. By stopping the water in one spot, it enables the water to sink into the ground.

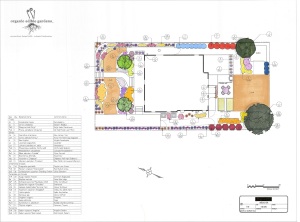

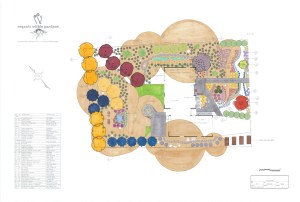

Carving out swales for a recent project in Purcellville, VA

Permaculturists are often fond of saying that the cheapest place to store water is in the soil. Indeed, it costs much less to dig a swale than it does to purchase and install a large-capacity water tank – plus with just a tank, you still have to deal with the problem of water runoff from the tank’s overflow. In addition to capturing stormwater, swales serve many other important functions. By planting the swale berm with trees and shrubs (preferably fruiting plants, but hey, we’re biased), you can increase the amount of available water in the soil to your plants. This increased water supply boosts growth and fruit set. Ben Falk of Whole Systems Design has discovered, over 10+ years of experimenting on his farm in Vermont, that trees and shrubs planted on swales often exhibit twice as much growth as the same species planted nearby on flat ground. Over time, the increased amount of water infiltrated into the soil can also regenerate aquifers and revive springs downslope, creating even more of a water resource for people, plants, and wildlife.

Even the chickens love swales.

Of course, swales are only one tool in the rainwater harvesting kit, and may not be useful for all yards or properties. A detailed study of climate, soils, property size and other factors is the best way to determine which techniques are best for any particular situation. Usually a combination of various techniques, appropriately sited, are the best way to go. As seen in the pictures above, we recently installed a network of both diversion and infiltration swales as part of a permaculture landscape in Loudoun County. We’re excited to see how these earthworks solve drainage and erosion problems and provide free irrigation to the gardens. We’ll post more information over time as these systems develop and grow!

References:

Bane, P. (2012). The permaculture handbook: Garden farming for town and country. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Falk, B. (2013). The resilient farm and homestead: An innovative permaculture and whole systems design approach. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Kinkade-Levario, H. (2007). Design for water: Rainwater harvesting, stormwater catchment, and alternate water reuse. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Lancaster, B. (2009). Rainwater harvesting for drylands and beyond, volume 1: Guiding principles to welcome rain into your life and landscape. Tucson, AZ: Rainsource Press.

Lancaster, B. (2008). Rainwater harvesting for drylands and beyond, volume 2: Water-harvesting earthworks. Tucson, AZ: Rainsource Press.