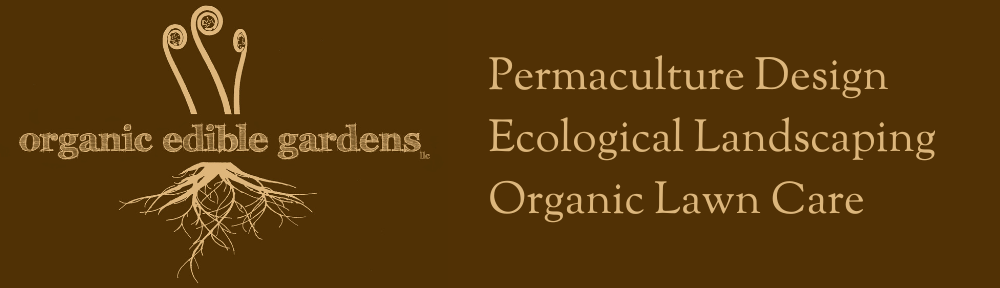

13 Acre Permaculture Homestead

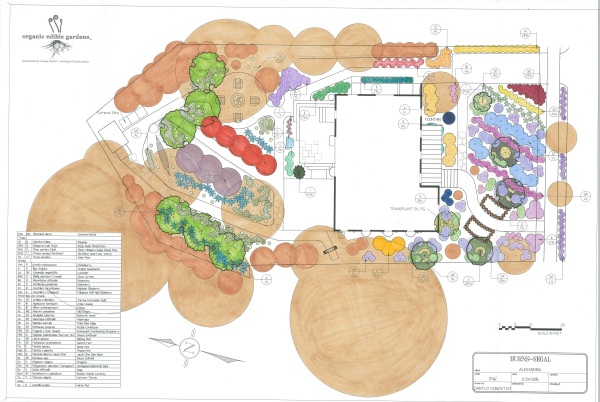

We designed zones 1 and 2 of a 13 acre permaculture homestead in Purcellville, Virginia. Zones 1 and 2 refer to the most visited and maintained areas on a property. They are also the areas closest to the house.

In the immediate areas surrounding the house we included a chicken coup with surrounding paddocks. Each paddock contains plants that are harvested at similar times of year. For example, one fenced in area contains summer ripening fruits, while another contains fruits that are ripe in the spring or fall. This way the chickens can be kept out of the gardens when the fruit is ripe, but can roam freely through the gardens at other times.

In the front of the house is an extensive annual vegetable garden laid out on contour with keyhole herb beds and keyhole perennial vegetable beds.

All of the water draining off of the back of the roof fills a pond designed for edible aquatic plants and native fish. The pond captures valuable fresh water and turns it into a beautiful and productive body of water.

Extending out further from Zone 1 we designed 2 large forest gardens containing nearly every fruit and nut that can be grown in this area. Accompanying the food producing trees and shrubs are nitrogen fixing, dynamic accumulating, beneficial insect attracting and pest confusing herbaceous perennial plants. The fruits and nuts include Peach, Apple, Cherry, Almond, Filbert, Pawpaw, Persimmon and various berries.

Lining the driveway are 12 English Walnut trees and 24 Mulberry trees, creating a shaded enclosed entrance to the property. The Mulberry trees act as a buffer to the plant growth inhibiting compound emitted by walnut trees called Juglone.

Extending further out from the driveway are two single row grape trellises accompanied by Rugosa Roses and Lavender. The roses and lavender not only add beauty to the front of the property but also aid in pest and disease prevention for the grapes.