Native, ornamental and edible plants provide a beautiful, enclosed sanctuary for this Alexandria residence.

For a while now, we’ve wanted to start profiling certain plant species here on our site. There are a few reasons for this: First, a lot of these plants are unfamiliar to American gardeners (outside of some permaculture circles, that is!), and they definitely deserve a bit more popularity for several reasons. Second, we want to show that functional plants (edible, medicinal, etc.) can serve very powerful aesthetic purposes in the landscape as well. We hope that you will enjoy these profiles as we post them, and that you gain an appreciation of these amazing plants!

Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) is a large shrub in the Elaeagnaceae family that is native to Europe and Asia – it can be found from Britain to Japan, Norway to the Himalayas. In the wild, Sea Buckthorn is typically found near the coast (hence the ‘Sea’ in its common name), growing out of cliffs and sand dunes. What is interesting is that by evolving to grow in these harsh conditions (sandy alkaline soils, exposure to salt, etc.), it basically has the ability to grow in nearly any soil and any conditions you can throw at it (wet, dry, near roads where they put down salt in the winter, etc.), which is great for gardeners in many different kinds of growing areas.

One of the reasons that Sea Buckthorn can survive in so many different kinds of conditions is that it, like other members of the Elaeagnaceae family, is what is called a nitrogen fixer. Basically, this plant forms associations with soil microorganisms (in this case, a genus of actinomycetes called Frankia) . The plant absorbs atmospheric nitrogen, which is not readily used by plants, and transfers it to its roots, where it is “processed” by the microorganisms (in exchange for plant sugars and nutrients) into a form of nitrogen which IS available for uptake by plant roots. What this means, is that the plant provides its own fertilizer. This fertilizer is available for use by other plants, too – when its roots die back (which happens naturally or can be encouraged by coppicing, as described below), or when it drops its leaves in the fall, the nitrogen concentrated in these tissues remains in the soil, available for uptake by any nearby plant. Having these nitrogen fixing plants in the garden can reduce or eliminate the need for external inputs of nitrogen and other elements commonly found in fertilizers.

Aside from providing a good amount of fertility to the garden, Sea Buckthorn can serve many other functions in the garden. It makes a great hedge for keeping out unwanted intruders (human, deer or otherwise) – it does have thorns, so avoid placing near paths or where children play. It is a very beautiful plant – silvery gray-green, almost needle-like foliage gives it a very Mediterranean-like appearance. When it bears fruit in the fall, the plant is literally COVERED with brilliant orange berries – very much like Winterberry (Ilex verticillata), a common shrub in eastern American gardens. We’ll talk more about the fruit below. Sea Buckthorn can get to be 10-20 feet tall if left to its own devices, but can be kept reasonably small by coppicing (cutting it to just above ground level in the winter when it has gone dormant) every few years. It is an excellent plant for holding together soil and preventing erosion.

Sea Buckthorn fruit is not very good fresh – the berries are very tart and astringent, but they make an incredible juice when steamed or pressed and then sweetened. They are incredibly nutritious, too – incredibly high in Vitamin C and Vitamin A, antioxidants, and healthy fatty acids. Jams, jellies and wines made from Sea Buckthorn are delicious. The fruit yields an edible oil which can be used for cooking, and is also used to make an inexpensive and easily produced biodiesel fuel. Other uses of the plant include medicines, cosmetics, charcoal, wood fuel, and yellow dye.

To conclude, Sea Buckthorn is an incredibly beautiful, useful, multifunctional plant that we think deserves more of a place in our gardens and landscapes. Stay tuned for more useful plant species profiles, there’s a whole world to cover!

On May 5, in celebration of International Permaculture Day, we participated in an organic gardening & raw food demonstration at a local resident’s home. Our contribution was an herb spiral demonstration.

An herb spiral is a well known permaculture technique for growing herbs in a very small space. Essentially what this does is take about 30 linear feet of growing space, and condenses it into a mound approximately 6 feet in diameter and 2-3 feet high. This allows for easy access to the plants from all sides without having to reach more than 3 feet from any side.

It also allows for the creation of microclimates – creating small spaces with slightly different growing conditions that are ideal for different plants. Plants that require more sun are placed on the top and south-facing aspects of the mound, while plants that like a little less sun are placed on the north side. Since the mound is watered from the top, and the water will run down the mound, plants that prefer less water are placed near the top of the spiral while those that like a little more water are placed near the bottom where they receive more water.

Herb spirals can be as simple or as complex as your desire warrants – they can be anything from a mound of soil with stones or bricks outlining the spiral, to spiral-shaped dry-stack stone walls filled with soil. Our purpose in building this particular herb spiral was to illustrate what anyone can do with a minimum of materials and effort – in this case we used bricks, pavers, and mulch that the resident already had onsite, the only outside inputs were about a cubic yard of topsoil, the plants, and some alfalfa meal for an organic fertilizer.

First, we marked the circular outline of the herb spiral bed, and dug out a small trench to sink in the landscape pavers for a border.

We then covered the interior of the circle with cardboard to act as a grass and weed barrier – the cardboard will smother the existing grass and prevent it from growing up into the herb spiral. Over a few months, the cardboard will decompose and add organic matter to the soil.

Next, we filled the interior of the circle with topsoil to create the spiral mound.

Once the mound was shaped, we used found bricks from the site to shape the spiral.

From there it was a simple matter of putting in the plants – in this case, rosemary, thyme, oregano, sage, lavender and chives – and adding a bit of alfalfa meal as a slow-decomposing organic fertilizer.

Add mulch and water the plants, and voila – you have an herb spiral. The whole process took about 30 minutes from start to finish.

It was a great opportunity to show people how simple, inexpensive, and effective permaculture techniques can be. We had a lot of fun and look forward to giving more demonstrations in the future!

This is a really cool project we’re doing for a great friend of ours, Lauren Liess of Pure Style Home/Lauren Liess Interiors. We’re really excited to build this beautiful garden for her family!

©2013 by Jon Storvick and Organic Edible Gardens, LLC

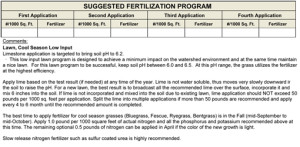

Our previous article on ecological lawn care was an introduction to how the ubiquitous and toxic-chemical-addicted American lawn can be transformed in a safe, non-toxic, eco-friendly manner. Now we’re going to show you a little of what that actually looks like in practice.

We have been working with one of our clients in McLean for several years now, designing and maintaining various plantings organically. However, they retained their existing lawn service, which treated the lawn with chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Despite all of the toxic chemicals, unsightly weeds still flourished in the lawn. They decided to try out our organic lawn maintenance service as an alternative. Here’s what we’ve been doing as part of the process of converting their lawn to an organic ecosystem.

First off, we needed a snapshot of exactly what the conditions were in the lawn ecosystem. We took several soil samples from the lawn areas, and sent them off to two different sources – one examined the chemical and nutrient levels, and the other analyzed the biological activity in the soil – bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, etc.

The chemical analysis indicated low levels of phosphorus, potassium and calcium, as well as a slightly lower pH than desirable. Organic matter was at 3.3%, where 6-8% would be more ideal.

The biological analysis indicated a much better microbial soil food web than we had anticipated – fungal and bacterial levels and diversity were good, but protozoa and beneficial nematodes were low. There were also higher levels of “pest” nematodes than were desirable.

We devised a strategy for increasing lawn health and converting to organic management based on these test results.

We arrived at the property in early April – we’ve had a belated Spring, so this was one of the first weeks where soil temperatures were high enough that we could proceed without harming the grass. Here’s a before shot of the lawn:

We began by organically removing much of the weeds in the lawn – hand removing taproot and bulb species like spring onions and dandelions, and flame weeding the rest (yes folks, this is safe, and we take all necessary precautions before using open flame in the landscape!).

We then gave the lawn its first mowing of the year, leaving the grass clippings in place. After mowing, we aerated the lawn to increase oxygen levels in the soil, decompact the hard clay, and allow for organic material to penetrate the soil surface.

After aeration, the next step is to topdress with lime and a good amount of compost.

We then spread the compost over the lawn.

After this is completed, we heavily overseed with our custom mixes (composed of various grasses, legumes for nitrogen fixation, and selected broadleaf species to fill open niches in the lawn ecosystem), and topdress with alfalfa meal, which slowly adds nitrogen and other nutrients through decomposition.

As we left, the lawn doesn’t look much different from when we started – but this will give it the initial start it needs to be healthy and organically maintained. In the future, we’ll be treating it with compost teas to feed the soil life, among other sustainable management techniques. We’ll keep you posted to show you how this new organic lawn turns out!

UPDATE 4/19/2013

After just 2 weeks, this is what the lawn looks like! Amazing!

For more information on organic lawn care, please visit the NOFA Organic Landcare website, or call Organic Edible Gardens LLC at 571-282-1724 for a free consultation.

©2012 by Jon Storvick and Organic Edible Gardens, LLC

Lawns are a hotly contested subject these days. Lawns have become the major defining feature of the American landscape. Yet, it wasn’t always this way. Up until the development of the suburbs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the lawn was the sole province of the extremely wealthy, who could afford to spare the land for non-utilitarian purposes (e.g. food production). Lawns have become synonymous with home ownership, but there is a hidden cost to our obsession with the “living carpets” that surround our homes.

“The American Lawn uses more resources than any other agricultural industry in the world. It uses more phosphates than India, and puts on more poisons than any other form of agriculture… A house with two cars, a dog, and a lawn uses more resources and energy than a village of 2000 Africans…. The lawn and its shrubbery is a forcing of nature and landscape into a salute to wealth and power, and has no other purpose or function.” – Bill Mollison, Introduction to Permaculture

, p. 111

Americans dump fertilizers and pesticides on their lawns in tremendous amounts. Since lawns do not infiltrate water very efficiently, most of these toxic chemicals run off into nearby storm drains and make their way into local watersheds where they poison ecosystems, animals, and humans. We will not give you statistics here, they are readily available with a brief Internet search. It suffices to say that lawns have a very large and very destructive impact on the environment.

An argument often put forward is to eliminate the lawn entirely in favor of lower-input landscapes, food forests, etc. While we certainly approve of these ideas, they are not the only option. Lawns do have their appropriate uses and functions, and we believe that they can indeed have a role to play in the sustainable landscape. As permaculturist Paul Wheaton says, “I think I have heard ‘grow food not lawns’ about a thousand times. I wish to advocate that the lawn is where children play, and where we put chairs to enjoy nature, and the place for yard sales. From a permaculture perspective I prefer ‘grow food in your lawns’: there are lots of edibles that would thrive there and tolerate the occasional mowing.”

While the edible lawn is somewhat beyond the scope of this article, we do wish to make clear that lawns in general can be sustainable and organically maintained. We’re going to tell you a little bit about how we do it here at OEG.

Grasses are plants too, and the ‘Right Plant Right Place’ mantra applies to the lawn as well. Most commercial seed mixes are based on a ‘one size fits all’ attitude, and species/cultivars of grasses in these mixes are rarely if ever tailored to site conditions – soil type and pH, climatic conditions, etc. Whether starting a new lawn from scratch or overseeding an existing lawn, it is important to select species and cultivars of grasses that are appropriate to the site. We use a mixture of several different grass species and cultivars, including tall fescues, American Buffalograss, Perennial Ryegrass, and Zoysia – all cultivars specifically selected for local site conditions, drought tolerance, and root patterns which partition the resources in the soil more effectively than monocultures. We also include small amounts of selected species of broadleaf plants in our lawn mix which do not interrupt the appearance of the lawn when mowed, and further utilize the soil resources, keeping water and nutrients in the soil where they belong. Seeding at the proper time of year ensures establishment with minimal resource inputs.

Weed control is a major issue with lawns in general, we’ve mentioned that lawn pesticides (including herbicides) are a major source of pollution in the Chesapeake Bay and elsewhere. The organic/ecological approach to weed control is quite a bit different than you might expect. It isn’t simply a matter of replacing toxic chemicals with slightly less toxic chemicals which come from “natural” sources. We try to understand the ecology of both weed species and of the lawn ecosystem as a whole, and design our strategies accordingly. Our lawn seed mix effectively partitions the resources in the soil, leaving no niches where weeds are free to grow. When weeds do appear, we remove them with either heat sterilization (destroying plant cells and preventing photosynthesis) or with hand removal where appropriate. We then seed the weed-free patches with our custom seed mix to immediately take advantage of the open niches. As a pre-emergent solution, we use an application of organic corn gluten meal in the early Spring, which prevents weed seeds from germinating, and has the great side effect of acting as an organic, slow-release nitrogen fertilizer for the lawn.

Fertilizing is another issue. We’ve already mentioned the use of corn gluten meal as both a pre-emergent weed control and as a nitrogen fertilizer. Other than that, there is really no need to fertilize the lawn, unless soil tests reveal severe deficiencies of other nutrients such as phosphorus or potassium, all of which can be remedied by the use of slow-release organic materials which break down naturally at the soil level. Topdressing the lawn with good, biologically-active compost in the fall also adds nutrients organically.

Cultural practices are important, too. Mowing is not a one-size-fits-all practice, either. Frequency of mowing should change with the growing season of the grasses, as should mowing height. In the Spring, when growth is lush and quick, more mowings at a lower height may be desirous, while less frequent mowings at a greater height are preferable in the summer, when growth is less vigorous and water needs are higher. Mowing higher in the summer allows the plants to grow deeper and more extensive root systems, which lessens the need for irrigation. Speaking of water, we think a well-designed and planted lawn should not have to be irrigated by anything other than rainwater, except in drought conditions. Healthy and biologically-active soil and proper plant selection should eliminate or significantly reduce watering needs.

Our region is known for its plethora of lawn pests and diseases, as well. From an ecological standpoint, it is plants that are already stressed that are more susceptible to pest and disease infestation. By keeping grasses healthy, we can significantly prevent most occurrences of pest and disease problems. For problems that continue beyond acceptable thresholds, there are organic chemical solutions that can be used as a last resort.

To summarize, it is possible to keep lawns as an integral part of a sustainable landscape, and through proper study and technique, to care for them in an ecological and organic matter. It really boils down to viewing grass as we do other plants in an ecosystem – healthy soil, proper plant selection, and growing in polycultures helps keep plants healthy and flourishing. For advice on growing your lawn organically, shoot us an email or give us a ring at 571-282-1724!