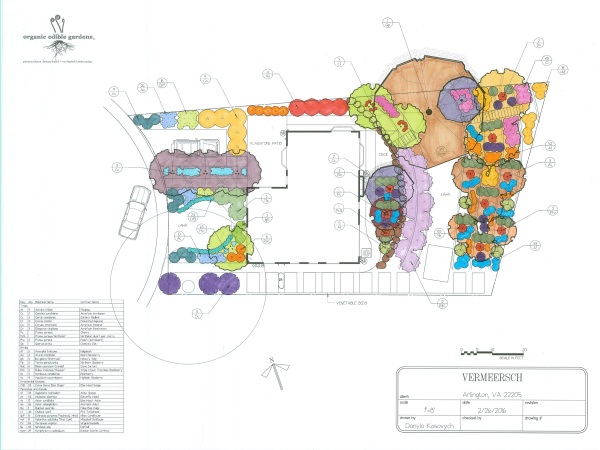

©2012 by Jon Storvick and Organic Edible Gardens, LLC

I’ve been doing lots of reading of late, especially in the field of agroecology. Agroecology attempts to view farming through the lens of ecological thought, viewing farm fields and so on as ecosystems. Much of this information is very similar to what we find in the permaculture literature, though agroecology is much more academically and scientifically based. One of the key elements of both approaches is the idea of growing in polycultures.

This is a healthy polyculture.

A polyculture can be defined as growing multiple species of plants together in a stand or patch. This stands in contrast to monoculture (growing a single plant species in a stand), which is the way we typically grow plants. A lawn is a monoculture. A corn field is a monoculture. A row of lettuces is a monoculture. The problem with monocultures is that they are unnatural – you simply don’t see stands of single species of plants growing anywhere in nature. The reason for this is pretty simple – groups of single plant species are highly vulnerable to pests, diseases, and other problems. A monoculture in nature would be decimated pretty quickly and would not survive.

This is a sterile monoculture.

Ecosystems are systems, obviously. They are networks of multiple species of plants (polycultures), animals, microscopic organisms, and other elements. While there is a food chain – life must eat, after all – generally no particular element suffers too much. Overall, the system is stable. This is why gardening in polycultures is a pretty good idea – we are lessening the possibility of our desired plants being overtaken by insects, diseases or competition from weeds.

Here are some of the benefits of growing in polycultures:

Decreased pest and disease problems– Including different plant species can confuse pest insects, leading them to ignore our crops. Since disease organisms also generally infect a single plant species, by including “buffer plants” between crop plants we block the vectors of infection. By including various flowering plants, we can attract beneficial insect predators that prey upon pests.

Increases in yields – While the yield of a single crop may be less than in a monoculture stand, if we include multiple crop species in our polycultures we can obtain total higher yields per square foot.

Decreased competition from “weeds” – By filling ecological niches in our gardens, we leave no room or resources available for undesired plants.

Increased plant health – By looking at how different plant species interact, we can design polycultures where each plant has a positive effect on the other (this is sort of an ecological version of “companion planting”). By including soil-building plants like nitrogen fixers (plants which form a symbiotic relationship with soil bacteria to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants) and dynamic accumulators (plants which “mine” nutrients from the subsoil and concentrate them in their tissues, making them available at the surface), we can create healthy soil for our plants. By choosing plants which have similar water requirements and complementary root patterns, we can effectively partition the available plant resources (soil, water, nutrients) so that each niche is filled and no plant needs to compete with its neighbor.

This is, of course, a very basic and incomplete treatment of the subject. For those that are interested in learning more about polycultures and how to design them, I strongly recommend you read both volumes of Edible Forest Gardens by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier. For a consultation on designing a polyculture that is right for your yard, call us at 571-282-1724 today!

by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier. For a consultation on designing a polyculture that is right for your yard, call us at 571-282-1724 today!